IMAGE: Peter Molyneux (22Cans)

‘Yes, in this immense confusion one thing alone is clear. We are waiting for Godot to come—’

– Waiting For Godot by Samuel Beckett

Over the last few days most every article written about Peter Molyneux and his company 22Cans has started with some variation on the same sentence:

‘Peter Molyneux has had a bad couple of weeks…’

(Well, that and the obligatory Waiting For Godot reference that self-loathing pun-junkies like me just can’t resist.) It’s the kind of catch-all observation that’s both undeniably true and open to whatever inflection the author chooses to apply to it.

For those sympathetic to Molyneux it’s a statement of solidarity – an industry luminary, a beloved, if occasionally over-eager creator has fallen into tough times, his reputation maligned by a string of unfavourable news reports. For those who have little patience for the designer, however, it’s a grim kind of schadenfreude. Finally, after years of reckless hyperbole, Molyneux is finally being brought to task for spruiking endless features, and entire games, that never come to fruition.

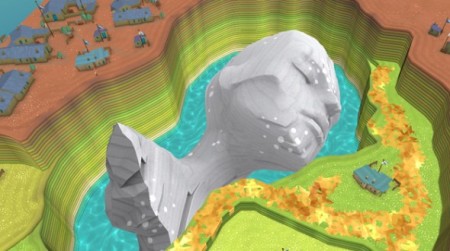

What triggered this whole mess was a series of glaring own-goals scored by Molyneux himself as 22Cans winds down production on Godus – the Kickstarter funded game that has yet to meet even its primary stated goals almost two years after it was supposed to have been completed. At the Fun & Serious Game Festival this past December, Molyneux announced that he was shifting his attention onto a new project, a smart device game called The Trail. Godus, he lamented, was a game that ‘lacked in narrative, progress and reward’, but The Trail (whatever it was) would be brimming with the stuff.

Everything snowballed from there.

Firstly, for a lot of people the tone of finality and regret rang some alarm bells. After all, whether his sentiments are genuine or not, Peter Molyneux has developed a reputation for disparaging his previous games whenever he wants to promote his next one (the Fable franchise being the most notorious example): ‘Don’t worry about that last game, that’s in the past; this next one is going to do everything that one failed to…’ Hearing this refrain from Molyneux again while mentioning his next project implied that he was drawing a line under Godus and abandoning it – something that came as quite a shock to the Kickstarter backers who were still waiting for a completed version of the game they had purchased. Predictably, social media and the Godus forums lit up with scorn.

Secondly, games journalists started combing back through the numerous promises Molyneux had made over the course of Godus, and the results were immediately troubling. Not only was the game still in an alpha state that lacked all of the multiplayer and competitive functionality Molyneux had been touting from its conception (in some interviews he had spoken of five hundred thousand players engaging simultaneously in dynamic battles; at present it remains a solo experience devoid of conflict), but some core promises from the Kickstarter campaign had been so walked back or ignored that the whole enterprise began to look suspicious…

After declaring that he had used Kickstarter specifically to avoid using a publisher, five months later, having met his funding goal, Molyneux signed with a publisher. The stretch goal of importing the game to Linux appears to have always been impossible. Molyneux’s own employees were posting on forums their dissatisfaction with the project and their regret that core elements of the game would never be completed. Even purchases supplementary to the Kickstarter pledge had not been honoured. Art books were neither produced nor delivered. A behind-the-scenes documentary had not been made. Some of the 359 students who paid for developer consultations and career advice felt they had been ignored.

Most gallingly, however, and inarguably the charge that has cast the biggest shadow on Molyneux, was the discovery that Bryan Henderson, the ‘winner’ of the Curiosity game that tied directly into the promotion of the Godus, had been effectively abandoned by 22Cans.

Henderson, the man repeatedly, publicly promised that his ‘life would change’ after winning the Curiosity challenge, was contacted by Eurogamer, who discovered that, despite Molyneux’s claims that Henderson would play a pivotal role in Godus (he would be ‘god of gods’; he would get a cut of the game’s ongoing profits) almost two years later he has so far received no money, had no direct involvement with the game, and been actively ignored by the company, who even stopped replying to his emails.

In an effort to hose down this controversy, Molyneux apologised to Henderson through the press, explaining that he was baffled as to how such an oversight could have occurred, and made assurances that – despite what principle members of the Godus development team had said – the game was still on track to implementing its online features. Henderson, he enthused, would definitely, eventually get to play the ‘life-changing’ role promised him.

But this latest round of interviews culminated in an exchange with John Walker at RockPaperShotgun who, rather than simply copying down the official quote, walked Molyneux through the litany of seemingly broken promises that the Godus crowd-funded project had already left in its wake. What resulted was so excoriating that Molyneux declared he was being hounded, and vowed to never again talk to the press.

That, he said, would be his final interview.

He said the same thing in an interview he gave to the Guardian, which he conducted almost immediately afterward.

And again to Kotaku, in the interview he did with them.

…And just in case the point wasn’t made strenuously enough, once more to a UK student newspaper called The Linc.

No more interviews! Except for those four and counting.

For those who claim Molyneux has cried wolf too many times, it all seemed like more feigned theatrics.

And so, in this roundabout way, we reach the point in which I too inevitably type the words:

Peter Molyneux has had a bad couple of weeks…

IMAGE: Godus (22Cans)

Before I get into my opinion – about this RockPaperShotgun interview, about the audience backlash, about the industry and Molyneux himself – I should probably lay out my own history to try to head off any accusations of bias.

For what it’s worth, I’ve got no horse in this race.

I was a great fan of Populous back on the Sega Master System, was intoxicated by the grimy cyber noir of Syndicate on PC, and had a good deal more fun with the Fable series than most it seems, but I was never a Molyneux faithful. Black and White, Theme Park, Magic Carpet, and Dungeon Keeper all passed me by, and aside from appreciating that he was a cheerleader for the industry, I never personally invested in any of the hyperbole that has so often made him a subject of ridicule.

‘Acorns that grow into trees’ and generations of children that live on after your character dies sounded wondrous, but at that time no one in the industry had even programmed convincing looking hair, so I was not exactly surprised when his promises fell short. What always struck me as more irritating was that the interviewers he would tell these things to never bothered asking how exactly any of it was possible. They just printed the words verbatim, shook their heads in wonder, and whipped up some anticipatory summary about how eager they were to see the final product.

Perhaps most significantly for this discussion: I neither participated in Curiosity, his grandiose ‘experiment’ in literal social click-baiting (to me it looked futile from its first announcement) nor did I invest in Godus, purported to be the successor to every one of his previous hits (the Kickstarter page describes it as part Black & White, part Populous, part Dungeon Keeper, etc). I did download the free Godus iPad app some months back. I remember thinking it was pretty but a little perfunctory, and deleted it once hit the predictable pay wall for advancement.

So when I approached the RockPaperShotgun interview, I was neither looking to defend Molyneux nor to see him kicked around for my amusement. What I found instead felt strangely inevitable. The natural end result of a cycle that has spun on for too long. It sounds trite, and the pun in the title doesn’t help, but what I found really did make me think of Waiting for Godot, and the uncomfortable tragicomic angst that plagues that play. Of characters locked into dialogue that now feels rote and overly familiar, emptied of meaning. Of people exhausted by the roles that they have no choice but to enact.

Defenders of Molyneux have criticised the interview as brutal and unfair. Walker was getting overly emotional, they say, being belligerent and twisting Molyneux’s words against him. That was not the way to speak to a games developer – an artist. Robin Parrish of Tech Times described it as an ‘assault’. Thomas Ella of Hardcore Gamer went to the hysterical length of labelling Molyneux the messiah in the article ‘The Crucifixion of Peter Molyneux Shows How Far We Have Fallen’. He describes Walker as having ‘nailed Molyneux to the cross again and again’, opining that:

‘We are not dealing with criminals or crooked politicians here; these are artists. Sometimes there will be mistakes, there will be unethical business practices, and there will even be games that failed to meet their creator’s lofty promises, but we are still talking about video games — about entertainment — and that cannot be emphasized enough.’

Voices such as these have waxed lyrical about what a grand shame it is that such a talented artist is now being chastened, unable to voice his ideas. This will stifle creativity itself, they warn. And indeed Molyneux’s response to the interview was to claim that Walker – and a hostile games media at large – were driving him out of the industry. Clearly he was being targeted in a smear campaign designed to tarnish his reputation and tear him down.

It’s an emotional appeal, and one that on first glance is hard to dismiss. Here is a guy who loves the medium and clearly loves talking about it. But to categorise it as an attack on an artist is a gross misrepresentation, one that obfuscates the real issues by appealing to the easy terrors of censorship.

Undeniably, it is a bracing interview. When the first salvo is ‘Are you a pathological liar?’ you can fairly safely assume that the follow up is not going to be, ‘So how do you juggle work and family?’ But nothing within it seemed cruel or unjust.

Whatever else you think of the piece, Walker wasn’t attacking an artist, his work, or his ideas. He didn’t slag off the dog in Fable 3 for having crappy AI, or label Theme Park a failure because it didn’t synch with Theme Hospital like Molyneux once promised. He was asking him – in his capacity as the head of a business – why his company had failed to deliver on goods that had already been paid for by consumers, such as the art books that have still not even been printed, or features like multiplayer that have now been denied due to financing decisions that Molyneux made with third parties. He was asking him why he told investors that he could produce a game in nine months when his own experience showed he had never turned one out in less than three years. Why he would knowingly ask for less money than he was already aware he would need.

IMAGE: Curiosity (22Cans)

He was asking him why a young man who had already been utilised as a piece of advertising – compelled by his ‘win’ to give interviews to publications like Wired, Game Informer, and several news outlets around the world – had subsequently gone uncompensated and ignored by his company. How he could possibly claim to still be overseeing a project if he had already announced he had handed it over to someone else – Konrad Naszynski, previously a Kickstarter backer who joined the company because he believed the game was in trouble.

Consequentially, the interview was a completely legitimate piece of journalism – even that confronting opening question. In Britain, and here in Australia, you see precisely such probing questions from journalists. Just last week an interview with the Australian Prime Minister, conducted by one of our foremost reporters, literally started with the query, ‘Are you a dead man walking?’

In fact, if anyone really wants to cry foul about Walker’s ‘journalism’, then really his only inappropriate moments were when he – clearly sympathetic to Molyneux – took him at his word, or reassured him. When Molyneux claimed to have made good on some of the forgotten student consultations, Walker replied,

‘I think what I’ve done there is fill in one [crack in the story], that’s brilliant news. I’m really glad that that existed and that you did it and that’s good.’

If he were really being an unfeeling bully, such late unsubstantiated excuses would have meant little.

The problem is that despite the occasionally exasperated tone of the interviewer, the only one Molyneux was really combating was himself. Walker was simply quoting back to him explicit promises Molyneux himself had made – often not even in the heady adrenalin of an interview, but written down, contractually agreed, and repeated in multiple venues.

So to me, this overprotective reaction from people who believe Walker stepped over some unspoken line – evoking Molyneux’s status as an artist as immunity from questioning; suggesting that holding an incorrigible day dreamer to account for straightforward business decisions is somehow killing his creativity – is more indicative of another larger problem in the industry, and gaming ‘journalism’ as a whole.

Because there is and should be an important difference between a promotional junket and asking a businessman to explain himself when it appears that might have committed the literal definition of fraud. It’s a distinction that Molyneux is clearly having trouble making, and it is frankly a little alarming that so many other commentators in the industry, wringing their hands about the mistreatment he has apparently just suffered, don’t appear to recognise it either.

IMAGE: Godus (22Cans)

Perhaps you can argue that the tone of the questioning was a little rough – but again, unlike the majority of the other interviews he would have had with gaming press, this was not meant to be a puff piece. This was not about each participant following along to the dance steps of a prearranged preview, where Molyneux had a checklist of features to mention about the product he was spruiking, and Walker was just hunting for a splashy lead. It was a reporter seeking answers to troubling questions, backing them up with research, and not accepting obfuscation and evasion in reply.

It’s exactly what journalism looks like in any other industry.

To his credit, Molyneux didn’t just take offence and hang up the phone – but that’s because even he knows he to get in front of the story before it swallows him whole. Walker wasn’t beating him up, he was giving him a right of reply; in many cases offering him the chance to clarify his own damning testimony.

That’s not to say that it isn’t still worth asking why so many other Kickstarters and games publishers have not been similarly castigated for shady practices. Why focus on an independent publisher like Molyneux when Ubisoft can advertise clearly phony footage of Watch Dogs in their pre-release marketing and slap embargoes on reviewers to prevent them mentioning the buggy, unfinished mess of Assassin’s Creed: Unity before consumers had made their purchases? Why not tear apart Randy Pitchford at Gearbox for making similarly lofty promises about Aliens: Colonial Marines, a game advertised with fake footage, farmed off to underfunded secondary studios, and released borderline unplayable? But that’s not the same thing as saying such questions shouldn’t be asked.

Lamenting that the entire industry has been apathetic to these issues in the past doesn’t mean that everyone should just give up, continue asking softball, prearranged questions, and agree to play nice. For too long this is an industry that has been beholden to utterly ridiculous trains of hype, where unfinished products are feverishly talked up. Where ‘reporting’ and advertising become inextricably mixed in previews and demos. Where visibly uncomfortable creators are prodded out onto the marketing treadmill to peddle their wares and soulless PR reps fake up enthusiasm for design features that they had nothing to do with, and don’t fully understand anyway. Where early access and pre-orders and season passes actively try to circumnavigate delivering a finished product that can be judged on its own merits.

Thomas Ella’s extremely silly reference to Molyneux’s ‘crucifixion’ is therefore rather revealing because I think it does exhibit (albeit accidentally) the problem in the gaming media that this whole situation has exposed, and why the backlash against Molyneux in particular has such resonance. Because until now the distinction between artist and businessman in video games has been unhelpfully, systematically obscured; and while many might argue that Molyneux is not the worst offender, by his own actions he is the most symbolic.

Because Molyneux made himself a god. A god of the gaming industry.

And people notice when gods come tumbling down.

IMAGE: Godus (22Cans)

There has been a communal mythologising of Molyneux over the years – partly something that he has cultivated, partly something projected upon him. His history of trading on impossible, patently loopy ideas is such common knowledge that it has even spawned a parody persona lovingly lampooning him on social media in the form of ‘Peter Molydeux’, and has given rise to an entire competition, the Molyjam, premised on trying to bring ridiculous, wilfully impractical concepts to life. He has occupied a lofty, indulged position in the industry not just because of his achievements in the past, but because he continues to be such a charismatic, mysterious subject.

It’s what makes him such an appealing interview. He seems open, unfiltered, unrestrained. Consequentially, industry commentators are always swift to describe him as charming. Just read this interview at the beginning of Godus’ development in 2012 in which Molyneux breaks into tears (something he had also done in a couple of other venues and on a pre-recorded Kickstarter video at the time), and the interviewer, describing him as the ‘godfather of god games’, seems utterly enamoured:

Personally, I think [the tears] came from the exact same place as Molyneux’s childlike excitement from earlier this year. He loves games. He loves the possibilities they present. He loves his creations. And even if they destroy him, he’s going to keep investing his heart, soul, and reputation into each and every one. “I think I will be doing games until the day I die,” he said. “At this rate, the way I’m burning through my life, I don’t see that I’ll be alive much longer.”

The tenor of this description is all too familiar. Molyneux is besotted with games – in love with them. He can’t be held responsible for getting carried away when he’s so deep in the throes of inspiration.

Never mind that (as a Kotaku article, ‘The Man Who Promised Too Much’, outlined) there are numerous anecdotes – some of which Molyneux tells himself – showing him in a far less flattering light. Lying in order to receive a gift of cutting edge computers under false pretences; throwing a stapler at an employee who argued for a higher bonus cheque; taking credit for features that were not his; embarrassing co-workers with impossible demands directly in front of the press.

He has even admitted, while excepting a BAFTA award that he frequently makes big promises that are complete fabrications in interviews just to keep reporters guessing:

“I could name at least 10 features in games that I’ve made up to stop journalists going to sleep and I really apologise to the team for that.”

Elsewhere he has acknowledged publically describing features that do not exist in the hopes that it will compel his employees to make them a reality.

And yet rather than leading reporters to question him more thoroughly in future, it just becomes part of the cycle; the contradictions just get folded into the grand narrative. Enigmatic genius or playful rapscallion? We’ll just keep describing the endearing glint in his eye and pretend everything he’s saying this time is true…

It’s a mutually beneficial arrangement for the industry because Molyneux makes – and actively courts – headlines. His promises make headlines. His apologies make headlines. The new promises he makes on the back of old apologies make headlines. Even a few weeks ago he warned Microsoft about over-promising on their HoloLens prototype and a predictable slew of articles, ripened with the irony of it all, rolled out.

But in the past three years the gulf between promise and product became too pronounced to shrug off.

IMAGE: Acorn Achievement, Fable Anniversary (Lionhead)

It is conventional wisdom that the Beatles’ biggest mistake was claiming that they were ‘bigger than Jesus’. Pride precedes the fall, and all that. But looking back, Molyneux seems to have tripled down on the self-deification after founding 22Cans. He wasn’t just bigger than Jesus. He was God.

He left Microsoft because he no longer wanted to be ‘constrained by what they can and can’t do’; he wanted to ‘ change the world and everyone will be happy.’ He was going to make the ultimate god game. He was going to make everyone in his audience gods. One lucky winner he was even going to make god of all gods, even cutting him a healthy slice of godly bounty.

Molyneux was declaring himself god of the god game that would spawn a god of gods amongst a network of infinite gods. The hype had built to a colossal, ludicrous level.

Pride precedes the fall.

Because ever since, Molyneux’s signature exaggeration has become less endearing. Since founding 22Cans and soliciting a small fortune through crowd funding he hasn’t just been delighting the press in the lead up to his big reveal – he has been perhaps been misleading the people who had already invested in his vision. These weren’t just apathetic potential customers whose attention he was trying to snare, they were the faithful who already believed in him.

Molyneux is delighted by the word ‘belief’. He believes he can make great things. He believes in the industry. He believes in games. Unfortunately, however, as the past few years have exposed, Molyneux sometimes also uses ‘belief’ as bait, robbing it of its meaning. Belief becomes a caveat. An excuse. Occasionally a weapon.

One of his popular refrains when getting called out for a promised feature that never appears is to regret that his enthusiasm so often gets misinterpreted as a promise. He shifts the blame from himself, the guy who said the words, onto the listener, the one who foolishly took them at face value. He effectively declares, ‘Well, you took the risk by believing me.’ But this ignores the fact that when he makes these statements, he explicitly declares them to be features. He’s not saying, ‘Wouldn’t it be good if…?’ or ‘This is what we’d like to do if we can figure it out…’; he says: ‘This is what we’ve done. This is coming.’

Believe me.

It’s a semantic sleight of hand that recurs again and again when one sifts through his innumerable apologies. Repeatedly, when it appears that he is accepting blame, or looking wistfully back upon mistakes, the fault is always subtly laid somewhere else. He didn’t lie, he just didn’t know what he was saying. Sure most of the goals won’t be met, but Kickstarter makes you say reckless things. He had to exaggerate.

And this is particularly true for the RockPaperShotgun interview in which his repeated mea culpas actually operate as attempts to make himself look all the more endearing. He’s sorry for being too honest. Sorry for sharing too much. Sorry for being so excited. For caring about what he does.

He’s sorry he tried so hard, but believe him, none of it is really his fault.

Blaming someone for dreaming too big, for trusting too much, feels mean. That’s certainly what Molyneux’s supporters argue in this whole mess. But it’s important to realise that what is coming under attack is not Molyneux, god of gaming. It’s Molyneux, god of marketing. The guy who knowingly traffics in deception to fortify sales. Who said that Fable: The Journey wasn’t on rails when it clearly, at every point, visibly was always on rails. Who said that Kickstarter was the only way to avoid publishers, right as he was signing up with a publisher. Who now admits the final days of crowd funding made him think,

‘Christ, we’ve only got ten days to go and we’ve got to make a hundred thousand, for fucks sake let’s just say anything.’

The people who cry foul at Molyneux’s treatment in this RockPaperShotgun interview are defending the dreamer, the artist, the sincere, if devoid of self-awareness enthusiast of the games medium. But he was not the one who was being interviewed. It was Molyneux who actively mixed those two figures up. And to continue to conflate the two just perpetuates the cycle of spin and marketing that gave rise to this muddle of a god complex in the first place. It furthers the uncomfortably reciprocal relationship that has masqueraded as games ‘journalism’ for too long.

And that is what this whole sad scenario has crystallised for me.

Experimentation is a vital part of creativity. It should be cherished and allowed to flourish – particularly in a medium still exploring and testing its fundamental expressive potential. But too often the videogame industry steps on the toes of its own innovation by promising too much too early – touting features and revolutions in game play not yet tested, funnelling everything into a bullet-points that can be rolled out as hyperventilating advertising promises before anything has even been coded. They become their own form of restraint on inspiration.

Molyneux began this downward spiral not by flying too close to the sun – as many have romantically tried to suggest – but by falling into a pattern of empty promotion, muddying the waters of creativity with marketing. Rather than experimenting with these ideas in his studio, or talking them through at games conferences, he would wind them inextricably into his sales patter. Essentially, what he was asking for was a license to workshop ideas in public, but with everyone playing along that the dreams were real, wilfully forgetting anything that he had said before, and suspending all expectation for the future. He was asking for a belief so absolute that risked becoming pure indulgence, where the promotion was more important than the work itself.

He made himself a god. He promised impossible things. But his need to stoke hope into white hot hype has set fire to his own icon, and threatens to burn the whole thing to the ground.

In Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot two characters, Vladimir and Estragon, stand awaiting a man called Godot who they have been told will meet them. They too believe. But after an eternity of waiting, with day after day after day of disappointment, of the same messages being spewed by the same messenger – not this time, next time for sure – their hope has finally faded to apathy. Words are empty. Promises unfulfilled. Sentences repeat ad nauseam.

Peter Molyneux has had a bad couple of weeks…

‘But in all that what truth will there be? He’ll know nothing. He’ll tell me about the blows he’s received and I’ll give him a carrot. …. But habit is a great deadener.’

– Vladimir, Waiting for Godot

In Godot there are no more gods left. Just a dead tree and the familiar sting of self-loathing for ever having believed in the first place.

IMAGE: Waiting for Godot (Sara Krulwich, The New York Times)