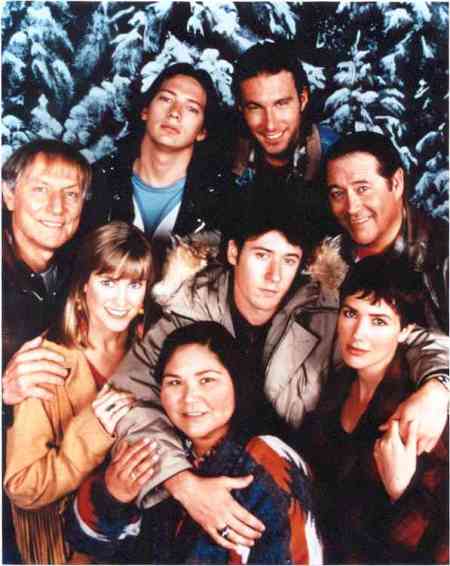

IMAGE: Arrested Development (from Entertainment Weekly)

Much can and has been said about the impending, miraculous return of a little show called Arrested Development – the fourth season of which is currently being filmed and is scheduled to be screened on Netflix later this year.* Admittedly the majority of what I would offer to such a discussion consists of me descending almost immediately into gleeful, froth bag hysterics, or winding up into a rage at the idiocy of the show’s premature cancellation – but that fact notwithstanding, much can be said. For those unfamiliar with the series, however, those perhaps looking on in curiosity as fans like myself squee with joy at every detail dribbling out of the production of the new episodes, it is probably quite difficult to comprehend how a failed sitcom could overcome such a protracted hiatus to make its Lazarus return (six years is an eternity in television, with every one of the principle actors moving on to new projects) – and even more, why at this point anyone should care this much that they have.

It is a simple truth that it is always difficult to summarise humour. Explaining why something it funny usually results in dreary treatises of clinical description that utterly strangles any possibility of joy from comedy. Nonetheless, when discussing a great sitcom, one often speaks of the moments that capture some truth about the series, a moment that can be seen to lift the show from hilarious to sublime. Perhaps the first paintball episode in Community where Chang enters in a John Woo blaze; maybe the moment of unspoken forfeit when Kramer slaps down his losings on the kitchen counter in Seinfeld’s ‘The Contest’; possibly meeting Dr. ‘Space Man’ in 30 Rock’s ‘Tracy Does Conan’; or having David Duchovny go all Basic Instinct on Larry in The Larry Sanders Show episode ‘Everybody Loves Larry’. In each of these instances, what is depicted on screen is so funny, and so perfectly encapsulates the sensibility of the larger text on so many different levels, that the show becomes immortalised as one of the defining works of narrative humour, and frequently they spring to mind when trying to explain that program’s charm.

For Arrested Development the show’s mercurial narrative overflows with such comparable beats, offering flashes of orchestral comic genius that leap out from the screen: GOB theatrically crying, ‘Return from whence you came!’ before hurling a dead dove into the ocean, for example; watching Charlize Theron ‘magically’ walk on water, only to have Tobias, on fire, unable to sink in that pool moments later; the family trying to run a fundraiser to combat the scourge of the disease ‘TBA’ (literally: ‘To Be Announced’); the many lessons one can learn through pranking with a one armed man; Buster’s run-in with a ‘loose seal’; watching the nation scramble to war at the threat of WMDs, only to ultimately deflate the conflict with Henry Winkler delivering the finest line-reading of his career: ‘Those are balls…’**

But personally, when I look back at the span of this series, the moment that cemented the show into a work of comedic transcendence, that symbolises everything that this anarchically imaginative narrative can accomplish, occurs in the third to last episode of season two, ‘Meat the Veals’. Here, at last (how did the show ever function without him?) we are introduced to another son of this eccentric family: a little man they call Franklin.

Mr. F.

But first: some history to help put this show’s miraculous return into context, and to justify its unique capacity to bring the dead to life…

As those already familiar with Arrested Development and its first three tumultuous years on air can attest, Arrested is the panacea of hope for every beloved televisual narrative that has been snuffed out before its time. For every Firefly unjustly ripped from the air; for every Deadwood that never got to play out its final beats; for every Law and Order that was smothered in its infancy (only twenty years?! Are you crazy NBC?!), there are precious few Futuramas and Star Treks brought back from oblivion. But Arrested Development – thank the almighty television gods – has now proved, against all odds, to be one.

In its original run (2003-6) it mystified the executives at Fox who seemingly looked on in abject horror as this award-winning, critical darling, with a rabid (if small) fan-base, underperformed in the ratings. For three seasons it skimmed along the edge of cancellation, each season’s order of episodes getting scaled back, from 22, to 18, to 13… to 0, with Fox itself eventually giving up trying to promote it completely, waiting over a month after it bothered screening the program regularly to callously dump the final four episodes in a glut all on one final night: Feb 10th, 2006, directly up against the Opening Ceremony of the Winter Olympics.

Throughout this battle to stay alive, however, Arrested retained its acidic wit, even masterfully integrating the issues of the show’s gradual downscaling and flagging ratings into the subject matter of the narrative: the truncation of the studio’s episode order was referenced in the series two episode ‘Sword of Destiny’ when Michael is seen arguing on the phone with a client who has suddenly decided to reduce the amount of housing they had ordered the company to ‘build’ from 22 to 18 (‘You initially told us to design and build 22 homes, now you’re saying 18 – that doesn’t give us enough capital to complete the job anymore. We’ve already got the blueprints drawn up and everything’); and in that same episode, the idea of moving the company to a new floor in the building is also raised – an idea perhaps referencing the show’s proposed timeslot change (moving them to a new floor in the building that ‘costs less’).

More overtly still, the brilliantly titled ‘Save Our Bluths’ (or: ‘S.O.B.s’) – an episode that had the family scrambling to save their business with a fundraiser awareness campaign – sarcastically contained every conceivable television grab-for-ratings staple possible: gratuitous celebrity guest-stars (Andy Richter played himself and his four identical brothers); extraneous 3D effects (put on your glasses now so that Gob can throw a tomato at you for no reason); a hyped-up, ultimately arbitrary ‘Which of these beloved characters will die?’ mystery (spoiler alert: it was the perfunctory extra who had only enough lines to establish herself as an unsympathetic racist); and contained several reminders of the narrative’s new primary mission statement, which sounded (as they almost certainly really were) like studio notes on the script: characters were repeatedly reminded that they had to appear more sympathetic, and have identifiable problems that could be easily resolved through a series of frivolous, ultimately heart-warming escapades. The episode even began with the masterfully earnest Ron Howard, narrator of the series, breaking the fourth wall by reminding viewers to ‘Please, tell your friends about this show…’***

Ironically, however, for a program that exhibited this kind of acute, snarky, meta-textual self-awareness, much of the comedy within the narrative stemmed from the characters remaining blissfully, hysterically unaware of their own foibles and failings. From oldest son GOB’s (George Oscar Bluth’s) cocktail of inferiority complexes that manifest themselves in overcompensatory pageantry (a stage magician with a penchant for travelling via Segue and wearing ‘Seven thousand dollar suits – Come on!‘), to youngest son Buster’s sheltered, indulged life (a man in his thirties who still wants to wear matching sailor outfits with his mother, and whose dating history stretches little further than his mother’s best frenemy and a torrid affair with his Roomba). From daughter Lindsay’s need to overcome her self-esteem issues through protesting and activism – no matter how ill-advised or contradictory (in one episode she advocated both for and against circumcision, in another for her brother’s right to ‘die’ via fake-coma), to granddaughter Maeby, a fifteen year old rebelling against her mother’s rebellion by landing a job as an enormously influential movie producer responsible for multimillion dollar budgets (her adaptation of The Old Man and the Sea, The Young Man and the Beach, surely lost nothing of the original’s pathos…)

Even central protagonist Michael, a figure who in any traditional comedy would play the straight man amidst this menagerie, is in fact a figure so distracted by his longing to be a ‘good guy’, to appear selfless and benevolent, that he is blind to his own selfishness and false sense of superiority. …And all of this is before one even touches on a character like Tobias Funke (never-nude, graft-versus-host sufferer, cross-dressing British housekeeper, ‘analrapist’, who repeatedly prematurely blue himself).

On every level this is a show concerned with its characters’ incapacity to see the truths of themselves, revelling in their escapades a peculiar subverted narcissism that borders on the demented. What truly set the show apart, however, was its capacity to revel in the fantasies of these characters to borderline delusional extremes. And it is at this point, in one of the series’ most absurd imaginative allowances, that Franklin appears.

GOB, it is revealed, created Franklin Delano Bluth in an effort to liven up his magic act with some light ventriloquist banter. He was a puppet, loosely ‘inspired’ by the somewhat controversial Sesame Street character Roosevelt Franklin. But unlike his muppet namesake, who it has been argued skirted the edge of racial sensitivity, Franklin Bluth blindly stampedes right over it. And so, moments after his ‘birth’, Franklin is offering GOB’s mother some ‘brown sugar’ and laying down some truths ‘whitey’ apparently wasn’t ready to hear. (…Although, as GOB admits, ‘African American-y’ wasn’t ready to hear them either.) Soon enough, GOB and Franklin are recording duets about being both ‘brothers’ and ‘not heavy’ (Franklin with his own microphone and headphones), and crooning witless, self-penned lyrics like:

It ain’t easy being white…

It ain’t easy being brown…

All this pressure to be bright.

I got kids all over town…

Like a surreal homunculus, Franklin immediately embraced his gift of life and began seemingly acting independent of his creator. Indeed, by the third season Franklin is so assertive that he is instrumental in helping solve a court case, and undertakes a bold new business venture that puts another (this time literal) feather in his cap…

To the outsider it might seem ludicrous that a puppet could be so imbued with life, or that anyone could fail to delineate between themselves and the inanimate object strapped to their wrist, but one of the defining attributes of GOB is that he is so starved for a kind of egomaniacal gravitas that he fully invests in this skewed anthropomorphism. What is even more extraordinary, however, is that everyone else invests in the reality of him too.

People talk to Franklin. They speak about him when he’s not there. George Sr., offended by a crack that Franklin has make about his wife, Lucille, reacts by strangling the puppet – not the incompetent ventriloquist who artlessly mouthed the comment. When Buster puts him on, Franklin lets out a swift tirade at matriarch Lucille, shouting: ‘I don’t want no part of your tight-assed country club, you freak bitch!’ – an outburst that takes Buster himself by surprise. Even Michael, the character most disinclined to encourage GOB’s flights of fantasy, periodically acknowledges the puppet’s individuality. While trying to get off the phone with GOB, he gives in to this bisection of personality (despite the fact that at this moment the character is literally nothing more than a voice on the line), saying: ‘No, I don’t want to talk to… Heyyyyy, Franklin.’

Franklin becomes symbolic of all the illusory excesses at work in this family’s dynamic, every impossible longing that they project upon the world, that obscures their reality: Tobias’ acting career; GOB’s desperation to be the new David Copperfield; Lucille’s life of entitlement and excess (her stomach cannot ‘handle’ curly fries). Franklin presents for them an imaginative focal point, a communal delusional indulgence in which they can all hubristically embolden their own fantasies.

But the moment in which all of this coalesces into the perfect nonsensical epiphany comes when GOB, desperate to please his escaped convict father, agrees to sneak him past a condo security guard in the back of a limousine. When the guard wanders closer to inspect the cabin and offers a friendly greeting, GOB offers a nervous hello, one that is followed immediately by Franklin leaping up and shouting, ‘I ain’t your daddy!! Hey, brother!!”

The guard – who is African American – looks down at what appears to be an offensive racial stereotype perched on the blithely ignorant rich Caucasian man’s hand. He tells GOB to pop the trunk and roll the windows down. For a moment everything stops a beat.

In the front of the limo, the nervous GOB fidgets desperately, and the camera zooms in on his face.

In the back of the limo, the fugitive George Sr. looks terrified, and the camera zooms in.

On GOB’s hand, his expression unchanged, Franklin Delano Bluth stares unblinking.

…And the camera zooms.

Throughout the entirety of the series, Arrested Development knowingly cultivated a mild cinéma vérité aesthetic. Ron Howard narrates the interactions of this family in a sincere, detached tone, as though describing the behaviour of snow leopards or water buffalo; boom microphones swing into view; editors insert footage and clippings that reveal salient information (the cutaway to Tobias’ ‘Analrapist’ business card remains a haunting warning against abbreviating occupational specialties). Despite being pushed further into the background of the viewer’s attention than in a show like The Office or Parks and Recreation (where people talk directly to camera), Arrested frequently used this documentary presentation to inform and propel the narrative, sometimes to speed up the exposition, sometimes for a swift gag; but here, in this one fantastical lens shift, this style reveals something far more.

Not only had the characters invested in the ‘reality’ of Franklin – ballooning out from GOB and his duo enterprises (duets; double-acts), through the family at large (‘Heyyyyy, Franklin…‘), to the wider public (Franklin is called as a witness in a court case, and is another time handcuffed as a hostile suspect by police) – but now, in that one ingenious zoom, the documentary crew invests in him too. This interlaced hallucination is so absorbing that it pulls others into its gravity and we watch them eschew the objective truth of this world and embrace the skewed irrationality of this deluded family, further endowing their imagination with substance.

Franklin was no longer an ill-proportioned Muppet copyright-infringement – he was suddenly a character with his own motivations and fears – one to be scrutinised with the ‘journalistic’ lens of the camera along with the other participants of this strange docu-drama. No longer were we watching GOB with a colourful sock on his hand; this was now GOB and Franklin, together again on another mismatched buddy caper, each with goals and motivations and a rich personal history.

Franklin – much as his self-titled album of duets suggests – comes alive.

Further, by laughing at the audacity and mania of this directorial decision, we, as the audience, seal the deal: this is Franklin. Mr. F. Worthy addition to the Bluth family bonanza, connectively given life by the collective comic unconscious, now left staring down the lens of the camera, shivering in fear lest he be discovered for the hysterically deluded fever-dream that he is.

And when a show has the capacity to breathe life into the wholly inanimate – to give sensation and autonomy to an ill-stitched glove with no anatomical scale – it has moved beyond simple farce and satire, and waded headlong into Dr. Frankenstein’s anarchic lair, so overabundant with imaginative fervour that it can defy such a simple inconvenience as ‘cancelation’, and reanimate the old in a blaze of the new.

So I very much hope to see Franklin back in the mix come the broadcast of season four. Hopefully, as I type these very words, his name is being etched on the filming call sheets. So come on, internet! Where are the real spoilers?! I already know that Liza Minnelli is confirmed to return, and Scott Baio is back; but have we heard anything from Franklin’s representatives? has his agent been approached? Pay him whatever he asks for producers! He’s worth every penny. And those tiny tracksuits aren’t cheap…

IMAGE: Arrested Development (Fox)

* In what has recently been confirmed to be a longer run of episodes than first announced. Glee…

** And while we’re at it: Henry Winkler merrily jumping over a shark? Priceless.

*** Indeed, beside the live-to air episodes of 30 Rock (which I intend to speak on sometime soon) there has probably never been a more elegantly self-reflexive moment of television than this episode, with more of a statement to make about its own purpose, and the mind-bending recursive descent that can occur when that window into the text’s production is explored.