IMAGE: As You Like It directed by Kenneth Branagh (Shakespeare Film Company, 2006)

Set your expectations to ‘shocked’. Prepare to be astounded. Because I am about to utter (no doubt for the very first time on the internet) the most original, brave, singular thought ever articulated:

I hate reality television.

I know, right? I’m so raw. So real. I just tell it like it is, y’all. Truth bomb. Finger snap.

Man, I should get my own show.

I guess I should clarify. I don’t mean to slag off the whole genre …or, since I guess it’s too big to be called a genre, the ‘form’? The ‘structure’? The ‘plague’? Lots of people love it – for innumerable reasons – and as a device it can take myriad shapes. Honey Boo Boo can hardly be placed in the same discussion as Making a Murderer; and the soapy freak show of the Real Housewives franchise is worlds away from whatever the hell Naked and Afraid is attempting to be (although when are we going to see Real Housewives: Sesame Street? ‘Elmo so mad Elmo almost run her down in Elmo’s Ferrari…’).

What bothers me is the overt artifice with which these shows are fuelled. The attempts to ape reality that are patently constructed. The artificial people having artificial conversations – be they the Bratz dolls of The Hills or the Deliverance cosplayers of Duck Dynasty. The concocting of zany, pre-arranged schemes. The leaning in to stilted, predetermined confrontations. The meet-ups in restaurants, or the drop-ins at someone’s start-up business to share wooden dialogue riddled with one-liners and rote exposition. ‘Surprise’ telephone calls where both sides of the conversation are somehow filmed. The spouting of rehearsed ‘spontaneous’ observations and manufactured realisations. All those constant, ceaseless reminders that everything depicted is a fabricated mise en scene; that even before the highly selective editing process has begun, a narrative is already being orchestrated that renders any sense of authenticity moot.

Indeed, this whole pretence has reached such a saturation point that it’s now no longer a secret these shows have writers. They might be called ‘showrunners’, and sure, they don’t type out dialogue to be repeated verbatim, but they do run story treatments, come up with loose plotlines, concoct scenarios, give shape and order to the action – and yes, offer one or two snappy lines of banter.

And this fakery doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing. Many people (my wife, for one) happily watch a platter of reality programming comfortably aware that it has, at the very least, been massaged by its editing, or wholesale invented for the cameras. Personally, I find it tedious because it turns the viewing experience into a meta-game. Rather than watching the show, you’re watching through the thin, shiny veil that covers the behind the scenes production meetings that designed the show. Any sense of ‘reality’ disassembles into a meat-puppet theatre, one so commonly understood that there are now scripted television shows like UnREAL based around this premise.

A year or two back, I was compelled (it felt like at gunpoint, but I do have a tendency toward the hyperbolic) to watch what was then a new reality program titled It’s All Relative. The show was centred around the family life of Leah Remini, onetime star of King of Queens and Scientology escapee.* And I have to confess, by the standard set in a post-Kardashian universe, it was comparatively inoffensive. Indeed, almost quaint.

Let me be clear: I still hated it. I still squirmed and sighed and begged for freedom – but that’s a personal taste issue. I’m sure for many others it was charming.

But what struck me at the time as one of the show’s virtues was its subjects’ unfamiliarity with the language of reality television. To their credit, the family being scrutinised – Remini’s immediate family and mother – were uncommonly awkward with the fabrication of the filming process. They were so conscious of the oddity of a film crew in their house that they would actually talk directly to the producers and sound techs as though they were new neighbours who had stopped by for a chat, commenting down the camera lens not only about what was being filmed, but the decision to film it. In a world where Kardashians keep multiplying through social media photosynthesis, it was comforting to still see people try to grapple with the invasion of a guy with a boom mike having his elbow in their fridge.

IMAGE: It’s All Relative (TLC)

In one scene, when a mock funeral for Remini’s mother had soured into a peculiarly melancholy affair (despite the zany music cues punctuating the soundtrack) Remini actually turned to camera, wiping tears from her eyes to ask, ‘Is this what you want, TLC? Is this what you want to see?’ She was joking. Ish. There was a laugh tangled in the crying, and the absurdity of the whole situation was never lost, but by referencing the artifice of the scenario, she punctured the constraints and manipulation under which the program operated. Clearly her mother didn’t just decide spontaneously to force her family to hold a living memorial for her; they didn’t all set a date and put on catering and get dressed in funeral clothes and all write eulogies on a whim. It was crafted. A display initiated for – and with – the film crew capturing it. Perhaps this humanising awkwardness went away with time, but I appreciated the meagre glimpse of authenticity it offered behind the facade.

The real issue I have with these programs arises however when their calculated artifice bleeds into reality. When asking an audience to playact dishonesty into ‘truth’ means we suddenly have to pretend that the Taylor Swift / Kanye West ‘feud’ is anything other than a cynical, mutually beneficial publicity stunt to be exploited for maximum exposure. Or, after several seasons of The Apprentice, people get duped into believing the pernicious, fatuous fraud that Donald Trump was ever a ‘successful, self-made businessman’, instead of a thin-skinned, paranoid, self-mythologising, narcissistic, pathological liar who once inherited an empire from his father and spent the next few decades flushing it away on an unbroken spiral of hysterically asinine failed business ventures and multiple bankruptcies (at least six). That a man with such a reverse-Midas touch that he spectacularly tanked everything he came in contact with, from an airline, to a travel agency, to a scam university, to a mortgage company (at the time of the country’s subprime mortgage crisis, no less), steaks, magazines, bottled water, vodkas and vitamins – a man who lost billions of dollars running his own casinos – that he was a successful business entrepreneur.

That guy.

If we have to swallow a lie that big, reality television should be a lot more fucking entertaining than it is.

In any case, all of this is just a protracted preamble to me saying that I was surprised, upon returning to As You Like It, at how many of the tropes of reality television Shakespeare employed, four centuries before it was even a genre

…Or a form

…Or a whatever the hell.

Because As You Like It is stuffed full of reality show fodder. It has backstabbing, and betrayal, and reconciliations. Its central conceit – aristocrats thrown into the wild – is pure Survivor. The whole thing ends on a ‘surprise’ wedding ceremony, where shocking secrets are revealed in public. Most every character is playing some sort of role to deceive, hide, or outwit their fellow outcasts, and above and uniting all of this, there is a general embrace of performative hamming it up and communal playacting.

In one delightfully convoluted moment, Rosalind – a woman masquerading as a man – is trying to disentangle herself from a pair of would-be lovers, Phebe and Silvius. Silvius loves Phebe, despite her treating him like garbage, and Phebe has fallen for the disguised Rosalind, who likewise treats her with contempt. And to a reality show cynic like myself, Rosalind’s summary of their circumstance, ‘He’s fallen in love with your foulness, and she’ll fall in love with my anger’ (III.5.68), could serve as the tag line for every season of The Bachelor and its ilk.

(You can look also to Much Ado About Nothing for more evidence of how much Shakespeare loves a good reality show plot. There’s its twisted fake funeral, the family squabbling, the vicious slut-shaming rumours, the zany schemes, and the will-they-won’t-they bickering couple whose romance everyone seems perversely invested in…)

Ultimately, As You Like It is soaked in the kind of pretence that drives me insane about reality television. But here, that willing embrace of falsehood becomes profoundly transformative, because ironically, it actually succeeds in rendering something true.

The plot (such as it is) may not sound like a playful comic romp. There are multiple familial betrayals and murderous plots; homes are ripped apart; loyalties sundered; choking declarations of unbridled hatred are made; most every sympathetic character is ejected into the wilderness to die – but the result is a celebration of farce and wilful play.

Primarily, the narrative concerns a gaggle of aristocrats who are banished from their homes into a nearby wood. Some embrace their imposed liberty, unfettered from the concerns of the civil world; others, by necessity, affect disguises to protect themselves from harm. But rather than descending into despair and savagery, playing out an Elizabethan Lord of the Flies, the characters meet this new, dangerous wilderness in the forests of Arden by giving license to their imagination. They literally start playing around. Enacting silly wooing games and writing poetry and dressing up to pretend. It can all seem, at first glance, a bit unhinged, but Shakespeare keeps the tortured, tragic thread that motivated this excursion throughout, just to remind the audience that we’ve not simply wandered off into some giddy fantastical dream.

There is the heroine, Rosalind, who, while wearing the disguise of a country boy, meets up with Orlando, a man for whom she had romantic feelings back in the city and who now appears to have similar feelings for her. While remaining in disguise, she convinces Orlando to let her ‘cure’ him of his love for Rosalind, by pretending to be her, and acting like a crazy woman. So Rosalind finds herself playing a man, playing a woman, playing crazy.

And not a television production crew in sight.

Given this theme of contrasting civilisation and wilderness, it is perhaps no surprise to say that As You Like It is concerned on every level with the question of nature versus nurture. What is it that defines us as people? Are we born bad – the fact one brother is a villain and the other a sweet tempered benefactor, merely a quirk of biology? – or do we rather learn our dispositions, becoming shaped by our experience? Do we merely affect an appearance of goodness to mask our intrinsic immorality?

For a while, in order to tease these questions out, the play seems to have it most every way. Two of the play’s brothers, Orlando and Oliver, appear to be diametric opposites, and yet both are the products of the same loving family, so Oliver’s cruelty, spite, and willingness to have his brother murdered, seems inborn; similarly, the two competing Dukes, the rightful Duke Senior and his usurping brother Frederick, who banished him with threat of death, were presumably raised together. But before the play lets us settle on this idea of an innate evil, both villains, Frederick and Oliver, prove themselves to be redeemable. Both, having left civilisation, are able to cultivate an inner peace that leads them to renounce their former behaviour and seek to genuinely better themselves in future. And either way, whether this is some elemental better human nature, or the promise of a newly acquired philosophy, the play opens up to the eternal, hopeful potentiality for change.

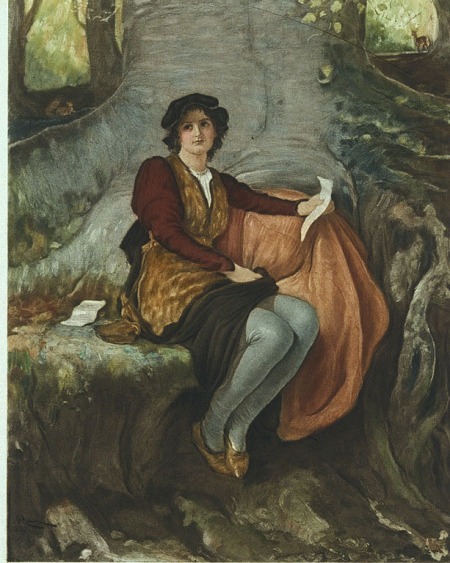

IMAGE: Rosalind by Robert Walker Macbeth (1888)

Despite this occasional, necessary cloud, it remains an exquisitely bright, celebratory play. Those filled with spite and jealous rage are able to be healed by the unburdened welcome of the wilderness. Brothers are able to forgive, to reconnect, to wish each other peace and goodwill. Lovers can embrace foolery to find within it deeper truth. Rosalind and Orlando get to shake out their playactings of love in disguise before they undertake the real thing, and the shepherd Silvius and his love Phebe (one hopes) get some perspective on their unhealthy emotional co-dependency, and actually agree to love someone who is capable of loving them back.

Shakespeare isn’t just detaching his characters from the recognisable world to make some lazy Garden of Eden reference (although that is overtly mixed into the imagery). This is not about sneering at the fall of man and idolising the ‘freedom’ granted by naïveté. After all, even though the two converted villains of the play vow to live more rustic, pure lives, most of the other characters gladly reclaim their lives in society. Instead, I think Shakespeare wants is to remember just how stifling adulthood, social pressure, the acquisition of wealth and esteem can be. It’s a daily fight for survival, as Orlando’s was at the beginning of the play, too swiftly propagated on competition and scheming, trying to outwit and outplay opponents you can see, and more tragically, those that you come to imagine. Even those you should consider family or friend.

By ejecting these characters into the wild, those societal shackles are abandoned. Life is no longer a competition, but an invitation to take solace in others, to support and encourage and give. Shakespeare writes the ultimate reverse-Survivor fan fiction. The gong is being rung for the eviction ceremony (is that how the show works?), but no one wants to partake.

And so, freed from the need to be grown-ups about everything, the characters embrace their youthful sides. Write mooney love poems; dress up and pretend; play-act getting married; chase each other around; fall asleep in the sunlight; sing songs. There is giddiness and gambolling, and fun (even in spite of there being lions roaming the land eating people, apparently.) All the crap, all the politicking and scheming and backstabbing, all those social institutions everyone believed were so integral back in the invisible prison of civilisation, are dissolved. Instead, they carry that which is crucial and unquantifiable with them: love, fellowship, and kindness.

It’s a hokeyness that Shakespeare himself acknowledges he is indulging. For much of the play’s run time it conducts a tongue-in-cheek interrogation of both its own structure (calling out its conventional failings) and its poetry (the hyperbole and disingenuousness verse relies upon for effect).** Orlando – despite loving Rosalind intensely, writes objectively bad poetry, scattering his meagre verse throughout the forest to the derision of all. Touchstone, wooing Audrey, says that all poetry is a fraud, ‘for the truest poetry is the most feigning’ (III.3.17-18).

Meanwhile, the plot seems to get forgotten in the salve of all this pretending. The real peril that the characters are in meanders away; major shifts in the narrative occur unseen, off-stage. When an as-yet unmentioned third brother of Oliver and Orlando rushes in at the end to exposition-dump that the danger of the usurping Duke Frederick has passed, it seems to be as unexpected an return to the narrative for the characters as it is for the audience.

And in Rosalind’s fourth-wall dismantling epilogue (which declares itself subversive for being delivered by a woman – or since women weren’t allowed to perform on stage in Shakespeare’s time, technically a man pretending to be a woman pretending to be a woman pretending to be a man…) – she cannot even be bothered to defend Shakespeare’s shapelessness narrative. Rosalind teasingly denigrates the play’s writing, saying she cannot ‘insinuate you in the behalf of a good play’ (V.4.202-3); instead, she uses her charm, with which the play is overflowing, to invite the audience to take from the production what they will – as they like it. They too are under no obligations.

Because this is not a play about story. Just like in reality television, the premise is merely the thinnest frame upon which to hang the real drama; the game less significant than the games the players played on one another. Fraud – and particularly poetic fraud – is here shown to lead to truth and growth, even in spite of itself. Here, unlike in the carnivorous scheming of reality television, giving license to falsehood brings out the best in us. Placed into artificial worlds we divorce ourselves from our engrained misbehaviours. Counter-intuitively, by pretending to be what we aren’t, we can reconnect with what we should be.

Rosalind fakes being a boy to lead the man she loves through his delusions of adoration to the clarity of self-awareness. Duke Senior, by playing at being a wild man, gets in touch with an unsullied vision of humanity where he can ‘feel not the penalty of Adam’ (II.1.5). Even the melancholic Jaques gets to be tickled by the verbal play of a fool, stepping, if only momentarily, out of his self-imposed funk.

Fittingly, it is therefore when the play indulges its most artificial moment that it presents its most elegant portrait of humanity. In the midst of what is in truth a bit of tedious stage business – literally Shakespeare needs to kill a few minutes so that Orlando can run off to retrieve his starving manservant Adam – the play stalls to have Jaques rhapsodise poetically about the lifespan of the average human being. Jaques, an insatiable depressive (a weathered The Cure t-shirt away from being the prototypical emo), has spent his time moping around the forest, in his words, sucking melancholy from melody and railing against the world, and here, to fill time, Shakespeare grants him one of the most genuinely moving descriptions of the inevitability of death, decay and mortal frailty, the seven stages of man:

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His Acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms;

Then, the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school; and then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow; then, a soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth; and then, the justice,

In fair round belly, with good capon lined,

With eyes severe, and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances,

And so he plays his part; the sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound; last Scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness, and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything. (II.7.140-67)

Seven ages of man; our inevitable, unavoidable, solemn march toward the grave’s oblivion, sans eyes, sans ears, sans everything. It will come, he says. But that’s for another day, the play suggests. And knowing what awaits need not deaden the beauty of youth and it virtue, but rather make it sweeter. If we are to be creatures always ensnared by larger constructs like society and temporality, then at least we can be aware of them, and free ourselves from their burden. Even if only in our minds.

IMAGE: As You Like It directed by Kenneth Branagh (Shakespeare Film Company, 2006)

On its surface, director Kenneth Branagh’s sumptuous version of As You Like It (2006) appears to bear little relationship to this falsified ‘reality’ television show conceit that I’ve been blathering on about. The production is set in a stylised pre-twentieth century Japan, with a group of English aristocrats. But this notion of play-acting a superficial facade is nonetheless central to the themes being explored, becoming uncomfortably problematic as the film proceeds.

In many ways it is a lovely production: lavish visuals; a score that is evocative and sublime; acting that is solid to exceptional across the ensemble. There’s a little less Rosalind (as played by Bryce Dallas Howard) than I would like as good portions of her dialogue appear to be excised, but national treasure Brian Blessed gets to portray both Dukes as twins, running the gamut of Senior’s benign saintliness to Frederick’s volcanic, paranoid psychosis, and Romola Garai, as Celia, is delightful, as always. The brothers Orlando and Oliver (David Oyelowo and Adrian Lester respectively) are both fantastic – Lester in particular gives emotional depth and complexity to Oliver, a character that is often little more than a moustache twirler until his last minute conversion. And hearing Kevin Kline as Jacques deliver the seven ages of man speech never gets old.

And Shakespeare can work wonderfully in Japan. Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957) is a reimagining of Macbeth, taking a Jacobean English play about an 11th century Scottish King and translating it seamlessly – marvellously – into feudal Japan, elevating all the perversions of honour and madness of the original text. But here there doesn’t seem to be a deeper thematic reason for transplanting the action of the story to a British trading outpost in Japan outside of aesthetic quirkiness.

A title card informs the audience that these are colonial traders who have set up a ‘treaty port’ during the nebulous late 19th century period of British-Japanese political relations. Taken just at face value, Branagh appears to have simply replicated the original play’s romantic rejection of society and its embrace of the rejuvenating lustre of the natural world in the forests of Japan rather than a mythic British wilderness (although ironically he still films it in England). And that’s nice in theory – the stuffy Brits are going to learn about real life by being exposed to another culture – but that doesn’t really manifest in the play. In its place, a lot of complex, thorny issues of cultural appropriation are evoked that threaten to become outright controversial.

To begin with, all the of the principle characters are played by western actors – including many of those in the supposedly Japanese peasantry that have multiple lines. Even Charles the wrester (here a sumo wrestler, natch) has a western manager who speaks for him. Secondly, although Branagh attempts to utilise the trappings of Japanese culture to allow his western characters to access a truth within themselves (an impulse coming from a complimentary, if misguided, place) in practice, aside from a pretty estate, some fine clothes, a zen garden, and a token, unspeaking monk, there is little indication that Japan has impacted these characters much at all. His principle characters remain western imperialist intruders into a culture that they are in the process of coopting as their own.

If I sound like I’m really down on the film – I’m not. It’s still lovely. It’s just a shame, because it feels like there is something of more substance to say in the work that is never fully articulated. That in this enchanting Shakespearean fantasy cultures can be respected and genuinely shared beyond the limitations of genealogy. In practice though, at best the Japanese aesthetic is a pretty but ultimately pointless coat of paint, at worst it risks playing as more of a celebration of imperialist assimilation and the coopting of a culture.

But it is beautiful, and well acted, and by the time Orlando has been attacked by some stock footage of a tiger, I am already in the thrall of Rosalind’s layers of playful fraud. Because here too, reality is joyfully bent to a happier end – you just have to be willing to ignore the bad, socially disheartening stuff for a moment, and indulge your imagination…

IMAGE: As You Like It directed by Kenneth Branagh (Shakespeare Film Company, 2006)

* * *

* It’s All Relative appears to have run for two seasons before ending in 2015.

** He even uses verse sparingly, with the majority of the interactions between the two lovers, Rosalind and Orlando, rendered in prose.

* * *

Texts Mentioned:

Book: As You Like It by William Shakespeare (ed. by H.J. Oliver, Penguin, 2005)

Production: As You Like It, directed and screenplay by Kenneth Branagh (Shakespeare Film Company, 2006)

Throne of Blood, directed by Akira Kurosawa, screenplay by Shinobu Hashimoto, Ryuzo Kikushima, Akira Kurosawa, and Hideo Oguni (Toho Studios, 1957)