IMAGE: Troilus and Cressida (BBC, 1981)

It is an understatement to say that Troilus and Cressida is a hard play to love. More accurately, it seems near impossible to find anyone who says they love it. Perhaps more than any other of Shakespeare’s plays Troilus and Cressida is little discussed, infrequently performed, and when spoken of in criticism, usually prefaced with some backhanded commentary (like this) about how baffling a ‘problem play’ such has this has always proved to be.* In his discussion of the play, Jack Vaughn repeatedly refers to elements of the plot and its characters as ‘botched’, ‘pointless’, ‘unsatisfactory’ and ‘confusing’ (at its very best he calls it ‘stageworthy’). Harold Bloom, in Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, calls it ‘the most difficult and elitist of all [Shakespeare’s] works’ (p.327).

I’m a little ashamed to admit that I had no idea what to expect from Troilus and Cressida before approaching it for this discussion. I’d not previously read it, nor seen it. I knew almost nothing of its plot, its characters, nor its reputation. Somewhere along the way I’d gathered that it involved a love story, though I ‘d never read Chaucer’s poem Troilus and Criseyde, upon which Shakespeare based his narrative. I knew it involved the Trojan War (with which I’m more familiar) but did not know in what capacity, or from which angle he approached it. So I went in fresh – arguably perfectly primed for the experience – and what I read, and then later saw, was legitimately haunting. And it would take months, and the daily dispatches of the American presidential race, for me to figure out exactly why.

But more on that later…

In Shakespeare’s canon Troilus and Cressida is a bizarre outlier – and it seems to revel in this disorientation. Described by some (including the First Folio of 1623) as a tragedy, by others a comedy (in the searing satirical vein rather than the playful or romantic), and still others as a semi-historical riff on Greek myth (the Quarto of 1609 calls it a history), Troilus and Cressida is altogether everything and nothing at once. It sets up multiple narratives, only to then thwart or undermine every one. It promises a love story (in its title, no less) that turns into less than a cheap one night stand and a torrent of bitter insults; concerns the most legendary war in human history, and yet reduces it to a gaggle of smug bros flexing at, shouting over, or ambushing one another like cowards.

It’s a play that I have come to learn has a bit of a curious history. It seems to have never been presented at Shakespeare’s The Globe during his lifetime – although that could suggest many things. Perhaps Shakespeare was not finished writing it to a producible standard (unlikely); perhaps its subject matter was potentially too inflammatory to be seen (given everything that happens in act 5 this might be possible); or it was performed there and the evidence is just lost. The first recorded production of the original play (an altered version by John Dryden played during the Restoration) was in the early 20th century, a time that seems fitting for the pessimism and contempt for war that infuse the work.

Ostensibly it is the story of two Trojans, Troilus and Cressida, whose burgeoning romance is cut short by the politicking of their city’s war with the Greeks – but this is all an overt misdirection. Really the plot concerns the war itself, and the character of the people engaged in it. The other source that Shakespeare clearly drew upon for inspiration, besides Chaucer, was Homer’s Iliad – and that poem, which proves to be a war book to condemn the futility of war, Shakespeare’s play is similarly critical, offering a scathing social satire.

The play’s myriad subversions of expectation begin from its opening second. As a prologue, Shakespeare has a narrator enter dressed in a suit of armour to give a brief account of the Trojan War. There’s the vow to ransack Trojan King Priam’s city; the romance between Paris and Helen; ‘the quarrel’; the disposition of the warriors; the layout of the camps; the doorways of Troy itself. He talks of the location and security of the two armies, the fortitude spurring them all on to impending hazard, but he also draws attention to his own curious costuming, and the play itself.

He has seemingly come to perform the thankless task of delivering exposition, informing the audience that the story is starting midway through the mythic events of the Trojan conflict, but more than that, he has wandered out on stage, dressed for war, to declare that war is not the principle thing on the menu. In actuality, his whole speech is a stage-setting distinctly obsessed with defences and deflection – both literal and figurative:

‘And hither am I come,

A prologue armed, but not in confidence

Of author’s pen or actor’s voice, but suited

In like condition of our argument…’ (‘Prologue’, 22-5)

Alongside describing the defences of each army, he is warning the viewer to be on guard too; he even admits that he doesn’t know if the play is any good, nor the acting that great. He warns the viewer to take nothing in this caustically ironic myth at face value.

Which brings attention to the next great quirk of this introduction: there’s no mention, at all, of the play’s titular characters. Unlike the introduction of Romeo & Juliet, which sets up the plight of the play’s lovers in a context of conflict and ruin – that of the corrupted ‘fair’ Verona – here the lover’s romance is not even name-checked. The table is set for war – and perhaps love – but it is all placed deliberatively in a state of potentiality:

‘Like or find fault; do as your pleasures are:

Now good or bad, ’tis but the chance of war.’ (‘Prologue’ 30-1)

War may or may not break out; love may or may not happen; the play may or may not be any good – that will all be up to us to discern. No wonder the Prologue so overtly alerts the viewer to the artifice of the production – the costumes, the writer, the performers – because the play itself is about to unfold, not as a battlefield, not even as a love story, but as an act of bewilderment.

It is about courtship amongst carnage; except that it’s not. About mythic warfare; except it deflates that too. In its title and its prologue, it intrigues us with the promise of wooing, and the tragic majesty of war, but will leave both unfulfilled, instead satirically exposing how empty the longing for both of these things is in a world of empty posturing.

For a story set in a war that famously ends with the sly infiltration of a walled city – the Trojan Horse – these negotiations of guarding and deceit are potent indeed. As the play proceeds it takes up the images of protection and shielding that pepper the introduction, but in doing so reveals the whole psychology of the war, and these two peoples, Trojans and Achaeans, to be twisted into paranoid defensiveness.

IMAGE: Troilus and Cressida by J. Coghlan (early 19th century)

The lovers, at first, both proclaim a need to hide their true feelings. Troilus claims that he has to hide his affection for Cressida (‘buried this sigh in a wrinkle of a smile’ (1.1.38); his ‘sorrow … is crouched in seeming gladness’ (1.1.39)); Cressida has to outpace her uncle’s wit when he tactlessly tries to set her up with Troilus, a man she’s not yet actually met. Being a woman in this world means remaining constantly at alert against attack. Cressida lies, she says,

‘Upon my back, to defend my belly; upon my wit, to

defend my wiles; upon my secrecy, to defend mine

honesty; my mask, to defend my beauty; and you, to

defend all these: and at all these wards I lie, at a

thousand watches.’ (1.2.252-6)

Almost immediately after this she reveals that she does in fact like Troilus a great deal, she simply feels she has to hide it from him (and everyone else) lest he lose interest in her for being too easy to win over (and her fears of his fickle affections will indeed be proved true).

Cressida observes:

‘Men prize the thing ungained more than it is’ (1.2.275)

And the play proves her right. Every longed for object – Cressida; Troy; Helen – is elevated to a state of impossible glory in the minds of those who claim to desire it. But the result of this affected detachment is, ironically, the devaluing of that which is pursued. In the case of the women being pursued, this belittling apparently occurs even in their own minds. Love becomes a boast; a lover a trophy to wave in the enemy’s face.

Diomedes, the Greek sent to exchange Cressida for Antenor (a Trojan prisoner being returned) sees through the artifice of all this ‘nobility’ and is willing to describe it as a bitter squabble over a ‘prize’ that is already devalued by the conflict. Helen, he says, is now either dishonoured or a whore, with the innumerable men who have died in her name only sullying her worth further (4.1.55-75).

‘She hath not given so many good words breath

As for her Greeks and Trojans suffered death’ (4.1.74-5)

And yet Paris, so enamoured with his ego-delighting prize, dismisses Diomedes’ words as envy, only continuing the pointless cycle of love’s debasement into pride.

The play is overstuffed with characters proudly displaying how little they know themselves. Ajax claims he doesn’t even know what pride is (2.3.146), and yet he is locked in a petty pissing contest with Achilles; Agamemnon condemns pride (2.3.150) despite his own arrogance being the cause of the rift between he and Achilles; Paris claims to be doing the honourable thing in not offering up Helen, despite it clearly being selfishness; and Troilus argues the moral virtue of keeping the stolen queen Helen – all of which is proved, later, to be a projection of his own fickle lust for Cressida. He calls Helen:

‘a theme of honour and renown,

A spur to valiant and magnanimous deeds,

Whose present courage may beat down our foes,

And fame in time to come canonise us’ (2.2.198-201)

And yet – as Hector suggests – Troilus is really just hopped up on his own hormonal longing for Cressida, and will abandon all these noble words of honour, and the supposed ‘glory’ of defending a stolen prize with blood, when Troilus’ own moment comes his fellow Trojans decide to trade Cressida away to the Greeks and he doesn’t fight for her. Not even with more pretty words.

Ultimately, this is a play to make you hate men. Simpering, cowardly, narcissistic Paris; braying, egomaniacal, thuggish Achilles; hypocritical, inconsistent Troilus; conniving, manipulative Ulysses; sleazy Pandarus; Ajax the blowhard idiot; Agamemnon the smug; Menelaus the belligerent and petty; even prideful Hector. Mankind, in all its forms, is cast in the most unflattering light. As Ulysses says, speaking of Achilles but proving a fitting summation of most every male character in the play:

‘possessed he is with greatness,

And speaks not to himself but with pride,

That quarrels as self-breath’ (2.3.164-6)

Each is so distracted with ‘imagined worth’ that they become lost in a fruitless battle with themselves.

Meanwhile women – when they are not being disingenuously exulted – are derided, discarded or damned. Those not placed upon dehumanising pedestals are subjected to other insult. When Aeneas arrives (Act 1, Sc 2) to announce Hector’s challenge to fight any Trojan brave enough to fight him, the challenge comes loaded with the insult that no Greek has a lover as fine as Hector’s wife, nor one worth defending as he does. Greek women aren’t worthy loving, he says.

Cassandra, who appears to see through all this idiocy into the madness of it all, goes ignored; Andromache is shushed and dismissed; Helen is squabbled over and objectified, both a jewel and an albatross around the Trojan necks, with no worth but to be lusted after, even by those who hate her; and Cressida, after being pimped out by her uncle, is traded like cattle into her enemies’ hands, is then condemned, both by her wavering, spineless ‘lover’, and seemingly the play itself. When she even entertains being wooed by one of her captors she is called unfaithful, false, stained, a whore, a depravity that debases all of womanhood (and that’s Troilus saying most of that – the guy who handed her over to his enemies without hesitation, having just slept with her – so, charmer) (5.2.127-31).

IMAGE: Troilus and Cressida (BBC, 1981)

Women are expected to maintain some impossible, saintly image in this play, to always defend the ‘virtues’ and ‘beauties’ and fantasies that men project upon them, while those same men go to every effort to tear down those defences, to undermine or ignore them. They are set with an impossible, irrational, doomed task, and then are condemned when they inevitably cannot satisfy these contradictory demands.

In this sense, it may well be Shakespeare’s most modern, if unrelentingly bleak, plays. In the wake of Gamergate, the uproar over a female Ghostbusters, and an unceasing industry of patronisingly sexist articles like the drooling interview with Margot Robbie in Vanity Fair, this searing indictment of entrenched patriarchy and systemised, celebrated misogyny retains all of its bite.

Amidst this ugliness, Shakespeare does not even offer the audience a sympathetic character with which we can identify. The closest, perhaps, are two characters who actively repel the audience. The first, Pandarus, is the play’s most peculiar character. Distractible, a little thick, so focused on trying to woo Cressida in Troilus’ name that he is blind to most everything else – even Cressida’s seeming indifference. And yet, if there is an audience equivalent in this play, a window into its fiction, it is he. When the whole narrative has seemingly abandoned Troilus and Cressida’s story in order to fiddle about in the Grecian camp, watching arrogant men poke one another’s pride, he is the only one left asking what is going on with the love story that gives the play its name. In a suffocating war, he still raves effusively for love. Like the audience, he seems to be the only one who came to see a love story; and so, by the end of this play’s action, he is left sick and mad, destroyed both body and soul in the face of so much hate and carnage and waste.

The second potential point of view character for the audience is Thersites, a guy so cynical and fed up with everyone around him that when faced with death his bid to live is: ‘I am a rascal; a scurvy, railing knave; a very filthy rogue’ (5.4.27). Essentially, I’m not worth killing because I’m a scumbag who doesn’t care about any of this war crap. And while that is a bold self-critique of the play and its themes, it makes it a difficult work (as the play’s prologue warned) to love.

It is probably this wilful discomforting of the audience that has led to this being one of Shakespeare’s least filmed plays. There are no major motion pictures based on his script, and the one production I found to view (there is another 2015 short film version that I’ve not been able to track down) comes from the BBCs television film series in which they were obligated to produce every one of this works.

Troilus and Cressida (1981) is worth watching, though, as it makes some curious choices in its staging, casting, and acting that only adds to the undermining of expectation that begins from the first moment the actors step on stage. The result is a series of stylistic choices that annoyed me at first, but that are clearly designed to create a jarring effect which ultimately won me over, even if my unease with the original work still remains.

Firstly, it has to be said that the mythic soldiers of Greece and Troy are rather a bit older than one might expect, and (to put it politely) considerably less battle-ready than the text itself would suggest. Across the board the acting is solid (if leaning a little too far into stagey pronouncement at times), but the performers’ age and appearance make all the talk of warfare and bloodshed and hand-to-hand combat comical. When war councils are called it looks more like a gaggle of AARP members passive-aggressively bickering over how to split the cheque at the early bird buffet. When Achilles turns up, the most brutal, merciless, unstoppable warrior of all time looks like a retired plumber. And although according to legend the character of Aeneas will go on after the events of Shakespeare’s play to gather the refugees of Troy, travel perilous seas, have a doomed romance with Dido, descend into Hades, invade Italy, and found the great nation of Rome, here he looks like Santa Claus in a duffle coat. After he delivers a message he looks like he needs a good lie down.

There’s no fury, no passion, no sense of urgency in any of them.

Clearly this was a deliberate choice rather than merely the natural result of a 1980s BBC casting call. Troilus and Cressida are played by comparatively younger performers, so it draws a bold visual distinction between the titular lovers and everyone around them: youth versus weary age; idealism versus cankerous cynicism; affection versus self-adoration. However, the consequence is a play that undermines its central characters from the very start – opening them up to the satire that courses throughout every aspect of the play.

Unfortunately, for me, this creates a stumbling block in the production. Rather than sharing Troilus’ misconception that his fellow warriors are men of nobility and honour, only to later be disabused of this misconception, we begin already mystified by his misplaced regard. For Troilus, his disenchantment with war and love and valour is four acts away; for the audience it occurs as soon as Aeneas shuffles onto stage and sighs in Act 1 Sc 1, robbing the play of its methodical unpacking of ‘heroic mythology’ by making the subtext immediately text.

Again, this is no doubt part of the desired effect, but by keeping the conflict so abstracted from the glib posturing of these heroes, by making them so comically unfit for war in the first place, to me, the play gives away the thematic twist all too early, meaning that the audience is never able to invest in the mythos being dissolved. We begin contemptuous of Troilus’ delusions long before his – and his society’s – hypocrisies are revealed.

IMAGE: Troilus and Cressida (BBC, 1981)

The set design and costuming are similarly a curious mix of anachronisms. There is more than a bit of Doctor Who to the production – not surprising for a BBC television production with a limited budget – with only two sets, a great hall in Troy and a Greek encampment, getting filmed from multiple angles to give an illusion of expansiveness. For its part, Troy has a Giorgio de Chirico vibe, filled with staircases that go nowhere, empty corridors into nothing, bare arches and plinths, with the whole environment having no sense of yet being under siege. The Greek camps are seething mud and campfires, cramped tents spilling over with throw pillows and prostitutes. There’s a marked contrast between the two spaces, but no real sense of how they relate to each other. The fighting between Trojan and Greek is sparse, filmed in awkward close up, or in the case of Ajax and Hector, as an afterthought slap-fight in the background. The only real sense that the Greeks are in any way inconveniencing or encroaching upon the Trojans comes in the final scenes when the dead and dying start piling up. Only then does the stark, museum lighting give way to a shadowy gloom.

Just personal preference, but I’m less in love with the costuming – this production chooses to ditch the ancient Mediterranean for more of a renaissance fair vibe – because the chipping away of the classical pseudo-historical myth of the Trojan War seems to me to be the point of the play. However, the alternate-reality perpetual-war evoked by this grab-bag of outfits and set design works well enough.

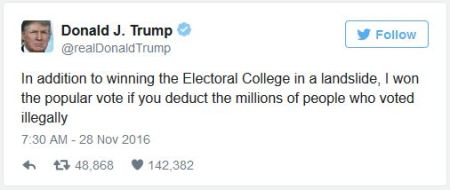

For a couple of months now, both before and after I saw this BBC version, I’ve been trying to diagnose what it is about Troilus and Cressida that so unnerves me. Yes, it is a dark satire. It sells itself on themes of love and heroism, only to actively denigrate those concepts; to prostitute them out, in the language of Pandarus, until, like him, they are diseased and vile. And for that, I admire the work, and the statement about humanity it makes, as callous and spiteful as that message proves to be. But there’s something more, something I find genuinely disturbing. And then, this past weekend, I read an article by George Saunders in The New Yorker called ‘Who Are All These Trump Supporters’ and it all clicked into place.

Saunders’ article is about the rise of Donald Trump throughout this presidential campaign, and the temperament of his most ardent followers. It explores both the grassroots supporters and the protesters that frequent Trump’s rallies: those that turn up to cheer, that parrot the talking points, that jostle and attack and whip themselves into a fury on both sides of America’s needlessly bifurcated political spectrum. As you can imagine, it is a dispiriting read. But what it reveals most is that there is an impulse – in the vile, intolerant rhetoric that Trump uses to enflame his followers’ sense of disenfranchisement; in those supporters’ willingness to overlook or excuse the repugnant behaviour of their presidential hopeful; and in the protestors’ willingness to descend into the same bigotry and rancour they claim to oppose – to willingly devalue the very principles one is hoping to celebrate, if it means claiming victory over your opposition.

As Saunders displays, Trump and his supporters want to protect free speech – unless someone else is saying something they don’t like. They want to make their country great again – by ignoring its founding principles of freedom and papering over the realities of its history. Protestors against Trump want to stop the racist slurs and invective – unless they are the ones using it. And everyone, everywhere, on both sides, is intent on propping up whatever their position is by making fraudulent assertions, claiming to be the most patriotic, and mistaking bullying aggression for strength. It’s Troilus and Cressida – only it is stripped of all the mythology and just lying bare and ugly for all to see.

As human beings we live in a perpetual state of opposition. We identify ‘Others’ and try to distinguish ourselves through the contradictions in our world views. Us and them. Male and female. Democrat and Republican. Trojan and Greek. But what we miss, in this blind, defensive posturing, this willingness to boil everything down to a false bipolarity of thought, is the similarities in our behaviours that bind us (even if sometimes only at the most base, lizard-brain, elemental level) to one another.

The consequence is that we now live in a time where public discourse itself seems to have devolved into a despairing farce. A time when news organisations blatantly perpetuate their own narratives and create their own ‘facts’. A time in which one of the two nominees running for control of the most powerful country on Earth – a candidate whose popularity resoundingly trounced his rivals – is a man that routinely demonises immigrants and Muslims and ‘elites’. Who insults women, mocks the disabled, and scoffs at prisoners of war. Who celebrates himself after national tragedies, advocates for war crimes, and looks to Mussolini and multiple white supremacists for inspirational quotes. A man so insecure and desperate to prove his machismo that he has to stop a presidential debate to assure that world that he has a wonderful penis.

IMAGE: Donald Trump at the University of Central Florida, March 2016

I said earlier that Troilus and Cressida might well be Shakespeare’s most modern play. Not only for its gender politics, but for the scathing catalogue it offers of a world of self-destructive misogyny, xenophobia, and feckless bluster, one that celebrates arrogance and ignorance and brutality in a cruel, empty campaign of fraudulent self-gratification. Sure, these have all been features of contemporary society for generations now – Shakespeare clearly saw some of it in the turn of the 17th century – but in the wake of the Trump Presidential campaign, now it seems downright prophetic.

Troilus and Cressida promises much – the great romance of Romeo & Juliet, the heroic battle of Henry V, the interrogation of human interiority of As You Like It, even the tragedy of Hamlet – and yet it thwarts these at every opportunity. It shows the emptiness of its ‘tragic’ heroes, reveals characters driven by blind obsessions and pride, reveals war to be an ugly, deceitful, squalid business, and exposes it’s ‘lovers’ as inconstant frauds. It is a play that dares you to hate it (again: that prologue), and yet in its constant frustration of expectation it becomes a fascinating, if disturbing, portrait of humanity’s natural inclination toward self-deception and fear.

IMAGE: Pandarus, Troilus and Cressida (BBC, 1981)

This play ends with a madman ranting about how diseased he and his world have become. Trump, the world-view he espouses, and the slurry of bloodthirsty bipartisan hate speech that he has gathered around himself, seem equally as contemptible.

Just not as honest.

IMAGE: Donald Trump

***

* The term ‘Problem Play’ was coined by F.S. Boas in 1896, and is used in reference to Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, Measure for Measure, and All’s Well That Ends Well – all plays that are too dark and filled with disturbing subject matter to be easily classified as comedies, and yet too playful in tone to be outright tragedies. Of course, the term ‘Problem Play’ is itself plenty problematic. Other titles are frequently added or subtracted from that list, including Merchant of Venice and The Winter’s Tale, and the term itself remains contentious, with many critics not recognising its validity at all.

***

Texts mentioned:

Book: Troilus and Cressida by William Shakespeare (ed. by Kenneth Muir, Oxford World’s Classics, 1982)

Production: The Complete Dramatic Works of William Shakespeare: Troilus & Cressida (directed by Jonathan Miller, BBC television movie, 1981)

Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human by Harold Bloom (Berkley Publishing Group, 1998)

‘Troilus and Cressida’ by Jack A. Vaughn, from Shakespeare’s Comedies (Frederick Ungar Publishing, 1980)